Informações sobre os testes cognitivos da Sensorial Sports: CogScore5, CogScore4m e Today.

(scrool down to access the English version)

Medidas de performance ou fadiga são as medidas mais importantes das ciências do esporte e da fisiologia (Currell & Jeukendrup, 2008). Existem fatores que contribuem para que esses testes sejam considerados bons testes, entre eles a validade e a confiabilidade.

A validade reflete a proximidade entre o protocolo de teste com a performance que está sendo simulada. Indicadores de validade englobam a capacidade de um teste prever a performance do atleta (e.g. um teste de corrida em esteira prever o tempo de percurso de uma maratona), assim como diferenciar pessoas com diferentes performances em uma atividade (e.g. jogadores de tênis profissionais versus jogadores de tênis em formação). A confiabilidade mostra se o protocolo provê resultados similares em diferentes medidas quando nenhuma intervenção é realizada entre elas.

Em 2017 e baseados nos conhecimentos supracitados, nós desenvolvemos uma avaliação de performance cognitiva em realidade virtual para o contexto do esporte e do exercício físico nomeada CogScore5. Nos avaliamos atletas de mais de 30 modalidades esportivas diferentes, desde atletas em formação de 9 anos de idade a pessoas com mais do que 65 anos de idade; medalhistas olímpicos, campeões panamericanos, sulamericanos e mundiais. Em 2020, nós desenvolvemos uma avaliação mobile (CogScore4) baseada nos conhecimentos científicos adquiridos pela versão em realidade virtual. As avaliações de performance cognitiva CogScore5 e CogScore4 são formuladas para contextualizar as avaliações à prática esportiva, principalmente porque atletas apresentam melhor desempenho em diversos testes neuropsicológicos do que não-atletas (e.g. Ando e Oda, 2001; Mori et al., 2002; Muinos & Ballesteros 2014; Nisbett et al., 2012; Vanttinen et al. 2010; Zwierko, 2008).

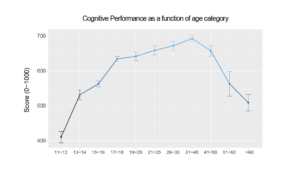

Indicadores de validade englobam a capacidade dos testes em diferenciar a performance de pessoas com base em padrões ubíquos. Entre eles, variações de performance associadas à idade são encontradas em quase todos os testes de performance, cognitiva ou não (e.g. Abbatecola et al., 2009 para performance física; Axelrod & Henry, 1992 para performance em tarefas distintas; Munoz et al., 1998 para performance em tarefas que envolvem movimentos sacádicos; Runge et al., 2004 para performance muscular). O padrão desses estudos é uma curva em “U” invertido da performance em função da idade. Isso porque habilidades são adquiridas tanto em função da aprendizagem quanto em função do desenvolvimento natural dos indivíduos, atingindo um pico que varia de acordo com a habilidade estudada, mas que normalmente ocorre entre o final da adolescência e o início do declínio ocasionado pelo envelhecimento natural dos organismos. Como exemplo deste declínio nas neurociências, espera-se que o hipocampo diminua seu volume em 1% a cada ano a partir dos 30 anos de idade. Essa diminuição é acompanhada pelo declínio de performance em testes de memória (Erickson et al., 2011). Dessa forma, esperávamos encontrar era a curva em “U” invertido da performance cognitiva medida pelas avaliações em função da idade dos avaliados, exatamente como demonstrado na Figura 1.

Figura 1. Médias e erro padrão da performance cognitiva geral medida pela avaliação CogScore5 em função de categorias etárias.

A confiabilidade, por outro lado, mostra se o protocolo estabelecido provê resultados similares em diferentes medidas quando nenhuma intervenção é realizada entre elas. Nós demonstramos em estudos anteriores (processo 2016/08321-9 da Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo) que as comparações entre as médias dos resultados da avaliação cognitiva e da reavaliação cognitiva para os atletas que NÃO foram submetidos a treinamentos cognitivos específicos não sofreram mudanças significativas após 5 semanas. Além disso, houve correlação entre os valores da avaliação e reavaliação dos indivíduos de cada grupo. Considerando uma amostra maior de indivíduos que foram reavaliados sem passar por treinamentos cognitivos específicos, nós obtivemos um valor de correlação intraclasse de 0,74, que corresponde ao intervalo de confiança de 95% para os valores de ICC da população. Este resultado SUGERE confiabilidade e reprodutividade dos valores obtidos a partir da análise criada para a avaliação de performance cognitiva. Estudos específicos sobre a confiabilidade da avaliação mobile estão sendo realizados.

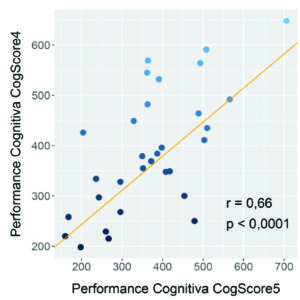

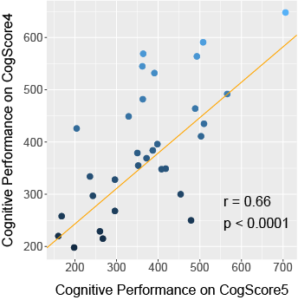

A performance cognitiva mostrou uma correlação bastante significativa entre os dados das avaliações CogScore5 e CogScore4, o que indica correspondência na mensuração da performance cognitiva de indivíduos pelos dois métodos (Fig. 2).

Figura 2. Performance cognitiva medida pela avaliação CogScore4 em função da performance cognitiva medida pela avaliação CogScore5.

Por fim, o Sensorial Today é um teste cognitivo desenvolvido pela Sensorial Sports para monitorar o estado cognitivo de atletas e pode ser aplicado para medir a fadiga, a recuperação e a prontidão cognitiva durante a preparação para treinamentos e competições esportivas. Este compartilha os mesmos fundamentos das avaliações mas, ao contrário das avaliações CogScore4 e CogScore5, que utilizam comparações do avaliado em relação à distribuição de performance da população, o objetivo do Sensorial Today é identificar flutuações de performance cognitiva do usuário por meio da comparação de suas medidas com uma linha de base móvel baseada na sua própria performance. Dessa forma, os alertas do sistema em relação a flutuações de desempenho identificadas podem refletir uma fadiga cognitiva causada por eventos pontuais (Blain et al., 2019; Bourne et al., 2019; Mejane et al., 2019), a recuperação (ou sua ausência) da fadiga mental (Hogervorst et al., 1999; Loch et al., 2019) ou a prontidão cognitiva (Bierman et al., 2009; Bolstad et al., 2006; Fletcher et al., 2014), de acordo com a rotina de utilização do aplicativo empregada pelo indivíduo e/ou profissional responsável.

Existem 3 possibilidades de alerta que indicam a diminuição do desempenho cognitivo. O alerta de flutuações negativas do desempenho da atenção (A), velocidade (L) e controle de impulsividade (I). A partir destes alertas, os atletas podem modificar a preparação para treinamentos e competições, ou mesmo a rotina que envolve atividades fora do ambiente esportivo.

Importante, os aplicativos da Sensorial Sports provêem informações que não substituem orientações, diagnósticos ou tratamentos médicos. Portanto, não podem ser utilizados com propósitos médicos. Todo o conteúdo disponível nos aplicativos (incluindo textos, gráficos, imagens e informação) deve ser utilizado apenas para propósitos gerais de informação. Em casos de dúvidas, a Sensorial Sports recomenda fortemente que o usuário consulte seu médico.

Information about Sensorial Sports Cognitive Tests: CogScore5, CogScore4m and Today.

Performance or fatigue measures are the most important measures in sport science and physiology (Currell & Jeukendrup, 2008). There are factors that contribute to these tests being considered good tests, including validity and reliability.

Validity reflects the proximity between the test protocol and the performance being simulated. Validity indicators encompass the ability of a test to predict an athlete's performance (eg a treadmill running test to predict the length of a marathon run), as well as differentiating people with different performances in an activity (eg professional tennis players versus players tennis player in training). Reliability shows whether the protocol provides similar results on different measures when no intervention is performed between them.

In 2017 and based on the aforementioned knowledge, we developed a cognitive performance test in virtual reality for the context of sport and physical exercise named CogScore5. We assess athletes from more than 30 different sports, ranging from 9-year-old trainees to people over 65 years of age; Olympic medalists, Pan American, South American and World Champions. In 2020, we developed a mobile assessment (CogScore4) based on the scientific knowledge acquired by the virtual reality version. CogScore5 and CogScore4 cognitive performance assessments are formulated to contextualize assessments to sport practice, mainly because athletes perform better on several neuropsychological tests than non-athletes (eg Ando and Oda, 2001; Mori et al., 2002; Muinos & Ballesteros 2014; Nisbett et al., 2012; Vanttinen et al. 2010; Zwierko, 2008).

Validity indicators encompass the ability of tests to differentiate people's performance based on ubiquitous standards. Among them, age-related performance variations are found in almost all performance tests, cognitive or not (eg Abbatecola et al., 2009 for physical performance; Axelrod & Henry, 1992 for performance on distinct tasks; Munoz et al., 1998 for performance in tasks involving saccadic movements; Runge et al., 2004 for muscle performance). The pattern of these studies is an inverted “U” curve of performance as a function of age. This is because skills are acquired both as a function of learning and as a function of the natural development of individuals, reaching a peak that varies according to the skill studied, but which usually occurs between the end of adolescence and the beginning of the decline caused by natural aging. As an example of this decline in neuroscience, the hippocampus is expected to decrease in volume by 1% each year from age 30 onwards. This decrease is accompanied by declining performance in memory tests (Erickson et al., 2011). Thus, we expected to find an inverted “U” curve of the cognitive performance measured by the tests as a function of the age of the subjects, exactly as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Means and standard error of general cognitive performance measured by the CogScore5 test as a function of age categories.

Reliability, on the other hand, shows whether the established protocol provides similar results in different measures when no intervention is performed between them. We demonstrated in previous studies (process 2016/08321-9 of the The São Paulo Research Foundation) that the comparisons between the averages of the results of our cognitive test and retest for athletes who were NOT SUBMITTED to specific cognitive training protocols did not undergo significant changes after 5 weeks. In addition, there was a correlation between the assessment and reassessment values of individuals in each group. Considering a larger sample of individuals who were re-evaluated without undergoing specific cognitive training, we obtained an intraclass correlation value of 0.74, which corresponds to the 95% confidence interval for the population's ICC values. This result SUGGESTS reliability and reproducibility of the values obtained from the analysis created for our test of cognitive performance. More robust and specific data is being collected in order to study the reliability of our mobile test.

Cognitive performance showed a significant correlation between the data from the CogScore5 and CogScore4 tests, which indicates a correspondence in the measurement of the cognitive performance of individuals by the two methods (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Cognitive performance measured by the CogScore4 test as a function of the cognitive performance measured by the CogScore5 test.

Finally, The Sensorial Today is a cognitive test developed by Sensorial to monitor the cognitive status of athletes and can be applied to measure fatigue, recovery and cognitive readiness during preparation for training and sports competitions. It shares the same fundamentals as the CogScore 5 and CogScore4 but, unlike them, Sensorial Today's goal is to identify fluctuations in the user's cognitive performance by comparing their measures with a moving baseline based on his or her own performance. Thus, the system's alerts regarding identified performance fluctuations may reflect cognitive fatigue (Blain et al., 2019; Bourne et al., 2019; Mejane et al., 2019), recovery (or its absence) of mental fatigue (Hogervorst et al., 1999; Loch et al., 2019) or cognitive alertness (Bierman et al., 2009; Bolstad et al., 2006; Fletcher et al., 2014). These alerts can be used to establish protocols for performance recovery implemented by sports professionals.

There are 3 warning possibilities that indicate decreased cognitive performance. The warning of negative fluctuations in the performance of attention (A), speed (L) and impulsivity control (I). From these alerts, athletes can modify their preparation for training and competitions, or even the routine that involves activities outside the sports environment.

Importantly, Sensorial's apps provide information that does not replace medical advice, diagnoses or treatments. Therefore, they cannot be used for medical purposes. All content available in the applications (including text, graphics, images and information) must be used for general informational purposes only. In case of doubt, Sensorial strongly recommends that the user consults his physician.

References

Abbatecola, A. M., Cherubini, A., Guralnik, J. M., Lacueva, C. A., Ruggiero, C., Maggio, M., ... & Ferrucci, L. (2009). Plasma polyunsaturated fatty acids and age-related physical performance decline. Rejuvenation research, 12(1), 25-32.

Axelrod, B. N., & Henry, R. R. (1992). Age-related performance on the Wisconsin card sorting, similarities, and controlled oral word association tests. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 6(1), 16-26.

Bierman, K. L., Torres, M. M., Domitrovich, C. E., Welsh, J. A., & Gest, S. D. (2009). Behavioral and cognitive readiness for school: Cross‐domain associations for children attending Head Start. Social Development, 18(2), 305-323.

Blain, B., Schmit, C., Aubry, A., Hausswirth, C., Le Meur, Y., & Pessiglione, M. (2019). Neuro-computational impact of physical training overload on economic decision-making. Current Biology, 29(19), 3289-3297.

Bolstad, C. A., Cuevas, H. M., Babbitt, B. A., Semple, C. A., & Vestewig, R. E. (2006, July). Predicting cognitive readiness of military health teams. In 16th World Congress of the International Ergonomics Association, Maastricht, Netherlands

Bourne, M. N., Webster, K. E., & Hewett, T. E. (2019). Is fatigue a risk factor for anterior cruciate ligament rupture?. Sports medicine, 49(11), 1629-1635.

Erickson, K. I., Voss, M. W., Prakash, R. S., Basak, C., Szabo, A., Chaddock, L., ... & Wojcicki, T. R. (2011). Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(7), 3017-3022.

Fletcher, J. D., & Wind, A. P. (2014). The evolving definition of cognitive readiness for military operations. In Teaching and measuring cognitive readiness (pp. 25-52). Springer, Boston, MA.

Hogervorst, E., Riedel, W. J., Kovacs, E., Brouns, F. J. P. H., & Jolles, J. (1999). Caffeine improves cognitive performance after strenuous physical exercise. International journal of sports medicine, 20(06), 354-361.

Hulleman, M., De Koning, J. J., Hettinga, F. J., & Foster, C. (2007). The effect of extrinsic motivation on cycle time trial performance. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 39(4), 709-715.

Loch, F., Ferrauti, A., Meyer, T., Pfeiffer, M., & Kellmann, M. (2019). Resting the mind–a novel topic with scarce insights. Considering potential mental recovery strategies for short rest periods in sports. Performance Enhancement & Health, 6(3-4), 148-155.

Mejane, J., Faubert, J., Romeas, T., & Labbe, D. R. (2019). The combined impact of a perceptual–cognitive task and neuromuscular fatigue on knee biomechanics during landing. The Knee, 26(1), 52-60.

Mori, S., Ohtani, Y., Imanaka, K., (2002). Reaction times and anticipatory skills of karate athletes. Human Movement Science 21:213–230

Muiños, M. & Ballesteros, S. (2014). Peripheral vision and perceptual asymmetries in young and older martial arts athletes and nonathletes. Atten Percept Psychophys 76:2465–2476.

Munoz, D. P., Broughton, J. R., Goldring, J. E., & Armstrong, I. T. (1998). Age-related performance of human subjects on saccadic eye movement tasks. Experimental brain research, 121(4), 391-400.

Nisbett, R. E., Aronson, J., Blair, C., Dickens, W., Flynn, J., Halpern, D. F., & Turkheimer, E. (2012). Intelligence: new findings and theoretical developments. American psychologist, 67(2), 130.

Runge, M., Rittweger, J., Russo, C. R., Schiessl, H., & Felsenberg, D. (2004). Is muscle power output a key factor in the age‐related decline in physical performance? A comparison of muscle cross section, chair‐rising test and jumping power. Clinical physiology and functional imaging, 24(6), 335-340.

Vanttinen, T., Blomqvist, M., Luhtanen, P. & Hakkinen, K. (2010). Effects of age and soccer expertise on general tests of perceptual and motor performance among adolescent soccer players. Percept Mot Skills. 110(31), 675-92.

Zwierko, T. 2008. Differences in Peripheral Perception between Athletes and Nonathletes. Journal of Human Kinetics. 19:53-62.